Padre Island, January, 2011.

I read “The Illustrated Man” for the first time yesterday. I have been interested in reading it for many years now, after having seen the movie starring Rod Steiger as a television re-run perhaps as far back as the 70’s. But recently I have been reading “The Martian Chronicles” and when I found myself over the last few days in the Midland, TX public library with time to kill, I thought I would investigate other Bradbury works (even though I have “The Martian Chronicles” in the car).

The movie bears little resemblance to the short story. In the movie a young man (as best I recall) is camping in the woods as he travels across country, when Rod Steiger staggers into the man’s campsite. Somehow (my memory is vague) Steiger reveals his body is covered with tattoos and tells the camper that the future can be seen in the empty spaces on his chest and back. At this point, the spaces on his chest and back form the framework for a series of four short tales, which, if I recall correctly, are other Ray Bradbury stories. I will not reveal the end, which I recall as being quite good.

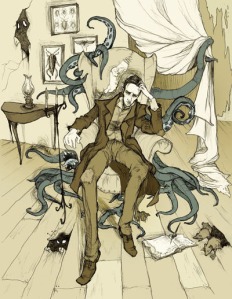

The actual story is not a collection of four stories, but a single tale of a man, William Philippus Phelps, who works erecting tents for a circus, but volunteers to become the tattooed man for the carnival sideshow after his weight balloons up to 300 pounds after he “stress-eats” because of the problems between himself and his new bride and he can no longer perform his job for the circus. Desperate to have any job at the circus, Phelps volunteers to have himself covered in tattoos. Someone steers him in the direction of an old woman who lives in the nearby woods and who does tattoos for free. He finds her and from her descrition (aged with eyes, nostrils, and ears sewn shut and living in a shack), she sounds very much like a witch. She inks the tattoos, which seem magically alive and writhing, but she also places a large bandage in the center of his chest and one in the center of his back and makes him swear not to remove the one on his chest for a week and the one on his back a week after that that. When Phelps does remove the one on his chest during the course of a show, it shows him strangling his wife, whom the tattoo witch had never seen. I won’t spoil the ending for you, which is quite enjoyable and reveals what is under the bandage on his back, because I strongly recommend that you read the story, which is only a few pages long.

Though Bradbury is, of course, world renown for his science fiction, this story falls much better into the horror genre. There is no science anywhere in story, only carnival folk, magical tattoos inked by a frightening witch, suspense, anger, and, ultimately, violence. The story is beautifully written with the language clear, concise, flowing, and simple yet powerful. I felt emotionally and intellectually drawn into the story and into Phelps’s life and felt empathy for his plight. This is an excellent work of horror, though its author’s fame as a demigod of science fiction undoubtedly has most people classify it erroneously.

Thoughts? Comments?