at the 2007 Scream Awards

Photo by pinguino k

Here’s the second batch of writing tips from Open Culture. They include tidbits from Neil Gaiman, Henry Miller, Elmore Leonard, George Orwell, and Margaret Atwood. Enjoy.

http://www.businessinsider.com/stephen-king-on-how-to-write-2014-7

Follow the above link to advice on writing from Stephen King.

There is a story that Ernest Hemingway wrote the following to win a bet with other writers that he could write the shortest story:

“For sale: baby shoes. Never worn.”

Even a little research on the Internet shows that there is considerable doubt that Hemingway wrote this story, with the earliest reference to it as a Hemingway work not appearing until 1991. There is also considerable evidence that the story existed in various forms as early as 1910, when Hemingway was 11 and well before his writing career began. Whatever the facts, it is an extreme example of the lean, muscular writing for which Hemingway was famous.

In an interview with The Paris Review (see The Writer’s Chapbook, 1989, pp. 120-121), Hemingway did say:

“If it is any use to know it, I always try to write on the principle of the iceberg. There is seven-eighths of it underwater for every part that shows. Anything you know you can eliminate and it only strengthens your iceberg. It is the part that doesn’t show. If a writer omits something because he does not know it then there is a hole in the story…First I have tried to eliminate everything unnecessary to conveying experience to the reader so that after he or she has read something it will become a part of his or her experience and seem actually to have happened. This is very hard to do and I’ve worked at it very hard.”

So “Baby Shoes” is a good example of Hemingway’s iceberg principle, even if he didn’t write it.

“Baby Shoes” is also a good example of what I like to think of as the Tao of writing (see my earlier posts): creating a story by a careful, strategic use of what is not said. No where in the story does it state that a couple had apparently been expecting a baby, that they bought shoes for it, but then something happened to the baby to cause its death, and now the parents want to sell the shoes. None of that is stated. It is all implied, but yet we know what happened–or at least we have a good idea of what happened, even if we do not know the concrete facts of the matter.

There are also other facets of the story that we can infer, albeit tenuously. From the fact that they bought baby shoes we can infer that the parents were probably eager to have the child. From the fact that the parents want to sell the shoes we can infer that they probably don’t want them around any more as a remainder of a painful experience, but at the same time they may want to see someone else make good use of them or that they are hard up for money.

But one question I have that concerns human psychology is why is it that most people can read these same six words and come away with the same perception of what occurred? Does it have to do with Jungian Archetypes floating around in each of us or is it that each of us has had the same broad experience(s) so that we can interpret these six words in a very similar way?

In the art of sculpture, those areas of a work that are empty, yet give the work its form, are called “negative space”. An example is the space between each of your fingers. If there were no space, there would be no individual fingers. In that sense, a story like “Baby Shoes” makes maximum use of what might be termed “literary negative space”.

It is not really the words that give this story its power, but how we psychologically connect the ideas behind the words that fuel this extremely brief, but epic and poignant tale.

This is part of the magic of writing: conjuring worlds out of nothing.

Thoughts? Comments?

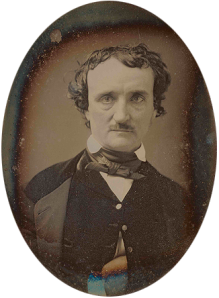

Guest Blog: ‘The Raven’ – Nevermore.

Interesting article, though I tend to disagree with his descriptions of what was going through Poe’s mind when he wrote this. Though I am not a skeptic, I tend to be skeptical when someone tells me in effect “yes, that is what he says, but this is what he meant…” Poe definitely hyped the bejeezus out of the poem (and his ego) by calling it the best poem ever written, but as for the rest…who knows?

Thoughts? Comments?

I was just sitting here trying to choose one of my many first drafts to work on for tonight, when I started thinking about the different “approaches” (for lack of a better term at the moment) to horror. By “approaches” I mean a very brief synopsis of a writer’s general outlook on or method of writing horror. Maybe a better way to express it would be to say the way the author approaches his genre (still not quite right, but I am getting closer to the idea).

An example would be to say that Poe’s approach was to bring out the horror in realistic situations (mostly, he did dabble in the fantastic occasionally). “The Black Cat” is about a murderer who unknowingly seals up a cat with the corpse of his victim. Nothing fantastic there. “The Tell-Tale Heart” is about a murderer whose conscience drives him to confession. “The Fall of the House of Usher” is about a family with an inherited genetic trait of hypersensitivity. So forth and so on.

Lovecraft’s approach was to spin tales of the fantastic, especially about a race of elder gods who once dominated the planet millions of years ago and of which mankind encounters remnants on rare occasion.

Stephen King’s approach is to plant an element of the fantastic among ordinary people in ordinary places and watch them react to it.

Clive Barker’s approach seems to be to take something that is fantastic, bloody, cruel, evil and gruesome and either drop it somewhere a single character can deal with it or bring it out of the shadows where a character can deal with it.

Seeing these different approaches in relation to each other makes me think about how do I want to approach an idea or a draft I have of a story. Do I want to drop the fantastic into the real or bring out the horror in the everyday or in realistic situations or can I come up with something else, my own approach, that is none of these? That is the challenge of creativity: to come up with something no one else has done. Maybe I can just go with the purely fantastic. Maybe I can try to find the real in the fantastic.

How many different ways are there to horrify an audience?

There is the real and the fantastic and all those subtle shades of gray in between the two. Can there be anything else?

Thoughts? Comments?

I was searching for a market for one of my stories today, when I came across “Strange Horizons”‘s list of stories they see too often (http://www.strangehorizons.com/guidelines/fiction-common.shtml). This is an interesting and entertaining article on (in my humble opinion) not only the types of fiction that “Strange Horizons” prefers not to see, but also the types of stories not to submit to any quality magazine: the tired, the clichéd, the preaching, the didactic, the sugary-sweet, the unprofessional, the polemic, the ranting, and the diatribes among a host of others. The list is so extensive, one could almost create a list of the characteristics of good literature by simply listing the antitheses of the types listed here. Yes, this list is oriented toward sci-fi writers, but if one were to replace the sci-fi specific terms with those of another genre, one would have a list of examples of mediocre to poor writing for that genre. Of course, neither this list nor any other can be completely exhaustive of all examples of either good or bad writing, but it would be an interesting mental exercise.

Thoughts? Comments?

I just want to post a few quick thoughts for the night on the topic of voice in narration versus narration in dialogue. The opinions I state here may change with time as I learn more of the art of writing, but these are my feelings for now.

Unless there is a specific reason to give the narrator an accent or flaws in his speech, the narrator’s grammar and speaking should be perfect. To my mind, this establishes a baseline against which the characters’ voices can be heard. It also establishes the author’s expertise and shows that the author knows what he/she is doing with regards to the language. If the narrator’s speech is perfect, then any accents or flaws or flourishes in the characters’ speech can be seen more distinctly. I believe the narrator’s voice (unless there is a specific reason for otherwise) should be simple, clear, and free from anything that might draw away the reader’s attention from the storyline. When I read, I am very focused on understanding the interaction of the characters, their solutions to problems and situations in the story, how the plot is developing and so forth. If the narration is overly ornate or full of irregularities or intricate devices and I have to resort to a dictionary to understand what is happening, my reading is interrupted, my concentration is broken, and my enjoyment of the story is diminished.

On the other hand, once the narrative baseline has been established, I can play with the character’s speaking styles in any number of ways and they will (hopefully) be more obvious because they stand in contrast to the narration. Again, unless a specific reason exists for doing otherwise, their voices should be clear and easy to understand. An example of this might be the case of a scientist, whose complex mind is shown by his use of scientific jargon and overly complex sentences. An example at the other end of the spectrum might be an illiterate bumpkin, who uses very simple words, bad grammar, and frequent vulgarities. Of course, you might also show that there is a hidden side to the character by their speech patterns. Suppose that the bumpkin mentioned above every now and then showed that there was more to him than met the eye by using scientific jargon or by having exceptional command of English.

I also like to toy with being able to distinguish characters by speech patterns and jargon. A sailor might use a lot of nautical terminology and Navy slang, but the reader might also be able to identify him through repeated use of a certain term. I used to have a friend that used the word “Whatever!” very frequently. His speech would be very easy to pick out in a dialogue of several people, even if the narrator did not state specifically who was speaking.

Thoughts? Comments?

I finished reading The Hellbound Heart several weeks ago. As noted previously, it is a truly terrific read. I suggest reading it after seeing the movie (if you have somehow repeatedly missed your chances of seeing “Hellraiser” over the last twenty or so years). Reading it beforehand will just spoil the movie, whereas reading it afterwards may enlighten parts of the movie.

I don’t have much to add to what I have previously stated, except that, if you are a student of storytelling, the book warrants a detailed examination for narrative technique as it exhibits some basic techniques of storytelling that Mr. Barker carries out very well. I could go through the book page by page and expound on each ad nauseam, but instead I will focus now on one that sticks in my mind.

I do not recall if this is in the movie, but toward the end where Kirsty is trapped in the “damp room” by Frank, she slips on a bit of preserved ginger lying on the floor enabling Frank to catch her. The method by which Barker establishes why that ginger is on the floor fascinates me.

Although I have one or two dictionaries of literary terms, I do not recall the name for this technique and I think of it as simply setting the stage for a future scene. It shows the foresight, planning, and attention to detail that must go into any good story.

Earlier in the story, after Julia has released Frank from the Cenobite hell and he has regained enough flesh that he can once again eat, he asks Julia for a few of his favorite victuals, including preserved ginger. At the moment I read this, I thought it was simply a natural but insignificant detail. Of course, I could not know then that that bit of ginger would skyrocket the dramatic tension later on in one of the novel’s most important scenes.

Anyway, that’s my post for the day.

I have been very negligent in posting anything over the last months, my daytime job and personal matters consuming much more of my time than usual. I have recently come to find out though, that many more people in my home town of Frankfort, KY, were enjoying my postings than I had known or even believed possible and sorely missed it during this hiatus. For them and all the others who silently enjoy my works, I shall endeavor to pick up the thread.

I have not lost my desire to write fiction, however, and I am currently trying to finish a sci-fi/horror novella that I started sometime back. The work is going well, but I am having to change some of my original concept to make it more exciting. I would like to make it as gripping as some have found my “Murder by Plastic” (published at www.everydayfiction.com), but that will be quite difficult for something as long as a novella. The part I find most challenging is to coordinate the details much as Barker did in the example I give above. I would expound on the subject, but I do not want to give away the plot or run the risk of some unscrupulous cur stealing my idea and publishing it before I do–particularly as I am so close to finishing it. After this I have another three or four unfinished works to bring to a close. I could probably write eight hours a day like Thomas Mann and still not be finished by spring.

Thoughts? Comments?

Here is a fascinating perspective on fiction by Neil Gaiman: ‘Face facts: we need fiction’ | Books | The Guardian.

The Works of Edgar Allan Poe, Volume 1. Yes, this link takes you to a collection of Poe’s works, but the reason I am mentioning it here is because the preface to this particular volume includes fascinating biographical notes and insight into the character of this master of horror that may help you understand the roots of his creative genius and how art sometimes came close to imitating life for Mr. Poe.

When you open the page, you may find yourself a little distance from the top of the article at the beginning of a section entitled “The Death of Edgar Allan Poe”. While this section is fascinating in its own right, scroll to the top for the entire preface. The works of Poe, beginning with the story of Hans Pfall, begin a bit down from “The Death…”

Here are a few more words for your horror vocabulary: “Seven Spooky Words for Halloween” at Dictionary.com – Free Online English Dictionary.

I apologize for the glitch, but apparently you cannot get to the Seven Spooky Words without having to flip through the Monsters of Literature and Folklore slide show. Both slide shows are enjoyable and quick, so I recommend visiting both anyway.

The other day I happened to find my copy of The Writer’s Home Companion (by James Charlton and Lisbeth Mark, 1987), which I had lost/forgotten some time back. I have been perusing it since and have found several anecdotes on various authors of horror, which had not captured my attention when I purchased the book, because I was not interested in writing horror at the time. I am quoting them below for your entertainment and consideration. They provide a few insights and lessons into the art and business of writing as well as into the lives of writers, if not in the art of horror specifically. If you would like to read more of the book, you can probably find a copy at your local library or half-price bookstore.

“Edgar Allan Poe opted to self-publish Tamerlane and Other Poems. He was able to sell only forty copies and made less than a dollar after expenses. Ironically, over a century later, one of his self-published copies sold at auction for over $11,000.”

“Stephen King sent his first novel to the editor of the suspense novel The Parallax View. William G. Thompson rejected that submission and several subsequent manuscripts until King sent along Carrie. Years later some of those earlier projects were published under King’s pseudonym Richard Bachmann, and one was affectionately dedicated to ‘W.G.T.'”

“Edgar Allan Poe perpetrated a successful hoax in the New York Sun with an article he wrote in the April 13, 1844 edition of the paper. He described the arrival, near Charleston, South Carolina, of a group of English ‘aeronauts’ who, as he told the story, had crossed the Atlantic in a dirigible in just seventy-five hours. Poe had cribbed most of his narrative from an account by Monck Mason of an actual balloon trip he and his companions had made from London to Germany in November 1836. Poe’s realistically detailed fabrication fooled everyone.”

“Robert Louis Stevenson was thrashing about in his bed one night, greatly alarming his wife. She woke him up, infuriating Stevenson, who yelled, ‘I was dreaming a fine bogey tale!’ The nightmare from which he had been unwillingly extracted was the premise for the story of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.”

“Amiably discussing the validity of ghosts, Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley decided to try their poetic skills at writing the perfect horror story. While nothing came of their efforts, Shelley’s young wife, Mary Wollstonecroft, overheard the challenge and went about telling her own. It began ‘It was on a dreary night of November that I beheld the Accomplishment of my toils.’ Her work was published in 1818, when she was twenty-one, and was titled Frankenstein.”

“Edgar Allan Poe was expelled from West Point in 1831 for ‘gross neglect of duty’. The explanation for his dismissal had to do with his following, to the letter, with an order to appear on the parade grounds in parade dress, which, according to the West Point rule book, consisted of ‘white belt and gloves.’ Poe reportedly arrived with his rifle, dressed in his belt and gloves–and nothing else.”

“Traveling along the Italian Riviera, Lord Bulwer-Lytton, done up in an embarrassingly elaborate outfit, acknowledged the stares of passersby. Lady Lytton, amused at his vanity, suggested that it was not admiration, but ‘that ridiculous dress’ that caught people’s eyes. Lytton responded, ‘You think that people stare at my dress and not at me? I will give you the most absolute and convincing proof that your theory has no foundation.’ Keeping on only his hat and boots, Lytton removed every other article of clothing and rode in his open carriage for ten miles to prove his point.”

If you have anecdotes about your favorite authors that you would like to share, please do.

Questions? Comments?

Yesterday, I happened across a good article at Vocabulary.com that cleared up something for me and so I thought I would pass along the info. Have you ever wondered about the difference between assure, ensure, and insure? Here is the answer: Assure/Ensure/Insure.

Here is another blog post that I happened across recently. You may find it of interest with regards to writing in general.

The Importance of Being Interesting | READ | Research in English at Durham.

Elmore Leonard passed away the other day and today a friend of mine posted this on Facebook in his honor. It contains some great tips on writing in general. Enjoy. Mr. Leonard will be sorely missed. Unfortunately, I have read only a small fraction of his works, but I do have one or two of his books on my shelves waiting to be read.

These are rules I’ve picked up along the way to help me remain invisible when I’m writing a book, to help me show rather than tell what’s taking place in the story. If you have a facility for language and imagery and the sound of your voice pleases you, invisibility is not what you are after, and you can skip the rules. Still, you might look them over.

1. Never open a book with weather.

If it’s only to create atmosphere, and not a character’s reaction to the weather, you don’t want to go on too long. The reader is apt to leaf ahead looking for people. There are exceptions. If you happen to be Barry Lopez, who has more ways to describe ice and snow than an Eskimo, you can do all the weather reporting you want.

2. Avoid prologues.

They can be annoying, especially a prologue following an introduction that comes after a foreword. But these are ordinarily found in nonfiction. A prologue in a novel is backstory, and you can drop it in anywhere you want.

There is a prologue in John Steinbeck’s ”Sweet Thursday,” but it’s O.K. because a character in the book makes the point of what my rules are all about. He says: ”I like a lot of talk in a book and I don’t like to have nobody tell me what the guy that’s talking looks like. I want to figure out what he looks like from the way he talks. . . . figure out what the guy’s thinking from what he says. I like some description but not too much of that. . . . Sometimes I want a book to break loose with a bunch of hooptedoodle. . . . Spin up some pretty words maybe or sing a little song with language. That’s nice. But I wish it was set aside so I don’t have to read it. I don’t want hooptedoodle to get mixed up with the story.”

3. Never use a verb other than ”said” to carry dialogue.

The line of dialogue belongs to the character; the verb is the writer sticking his nose in. But said is far less intrusive than grumbled, gasped, cautioned, lied. I once noticed Mary McCarthy ending a line of dialogue with ”she asseverated,” and had to stop reading to get the dictionary.

4. Never use an adverb to modify the verb ”said” . . .

. . . he admonished gravely. To use an adverb this way (or almost any way) is a mortal sin. The writer is now exposing himself in earnest, using a word that distracts and can interrupt the rhythm of the exchange. I have a character in one of my books tell how she used to write historical romances ”full of rape and adverbs.”

5. Keep your exclamation points under control.

You are allowed no more than two or three per 100,000 words of prose. If you have the knack of playing with exclaimers the way Tom Wolfe does, you can throw them in by the handful.

6. Never use the words ”suddenly” or ”all hell broke loose.”

This rule doesn’t require an explanation. I have noticed that writers who use ”suddenly” tend to exercise less control in the application of exclamation points.

7. Use regional dialect, patois, sparingly.

Once you start spelling words in dialogue phonetically and loading the page with apostrophes, you won’t be able to stop. Notice the way Annie Proulx captures the flavor of Wyoming voices in her book of short stories ”Close Range.”

8. Avoid detailed descriptions of characters.

Which Steinbeck covered. In Ernest Hemingway’s ”Hills Like White Elephants” what do the ”American and the girl with him” look like? ”She had taken off her hat and put it on the table.” That’s the only reference to a physical description in the story, and yet we see the couple and know them by their tones of voice, with not one adverb in sight.

9. Don’t go into great detail describing places and things.

Unless you’re Margaret Atwood and can paint scenes with language or write landscapes in the style of Jim Harrison. But even if you’re good at it, you don’t want descriptions that bring the action, the flow of the story, to a standstill.

And finally:

10. Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.

A rule that came to mind in 1983. Think of what you skip reading a novel: thick paragraphs of prose you can see have too many words in them. What the writer is doing, he’s writing, perpetrating hooptedoodle, perhaps taking another shot at the weather, or has gone into the character’s head, and the reader either knows what the guy’s thinking or doesn’t care. I’ll bet you don’t skip dialogue.

My most important rule is one that sums up the 10.

If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it.

Or, if proper usage gets in the way, it may have to go. I can’t allow what we learned in English composition to disrupt the sound and rhythm of the narrative. It’s my attempt to remain invisible, not distract the reader from the story with obvious writing. (Joseph Conrad said something about words getting in the way of what you want to say.)

If I write in scenes and always from the point of view of a particular character — the one whose view best brings the scene to life — I’m able to concentrate on the voices of the characters telling you who they are and how they feel about what they see and what’s going on, and I’m nowhere in sight.

What Steinbeck did in ”Sweet Thursday” was title his chapters as an indication, though obscure, of what they cover. ”Whom the Gods Love They Drive Nuts” is one, ”Lousy Wednesday” another. The third chapter is titled ”Hooptedoodle 1” and the 38th chapter ”Hooptedoodle 2” as warnings to the reader, as if Steinbeck is saying: ”Here’s where you’ll see me taking flights of fancy with my writing, and it won’t get in the way of the story. Skip them if you want.”

”Sweet Thursday” came out in 1954, when I was just beginning to be published, and I’ve never forgotten that prologue.

Did I read the hooptedoodle chapters? Every word.

Writers on Writing

This article is part of a series in which writers explore literary themes. Previous contributions, including essays by John Updike, E. L. Doctorow, Ed McBain, Annie Proulx, Jamaica Kincaid, Saul Bellow and others, can be found with this article at The New York Times on the Web: