Tag: Shelley

Notable November Horror Releases

Here’s another selection of horror films due out this month.

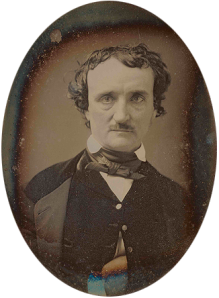

Review of “The Vampyre” by John William Polidori

1795-1821

(from Wikimedia)

Today I finished reading “The Vampyre” by John William Polidori. Polidori was a friend of Lord Byron and wrote this story during the famous writing contest between Byron, Polidori, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Mary Shelley, in which Mary Shelley wrote the initial draft of “Frankenstein” (see my post on Polidori and “The Vampyre” dated July 12, 2013). Tonight I wrote up a quick review for Goodreads, which I have pasted here for your enjoyment. I gave the story three stars out of five.

“The action was somewhat fast moving and the ending unexpected, but the plot is rather simple and the narration is hampered by a lack of dialog. There are probably less than five lines of dialog in the entire story of 9,223 words (I copied and pasted the story from the Project Gutenberg version minus the “Extract of a Letter from Geneva” and the “Extract of a Letter Containing an Account of Lord Byron’s Residence in the Island of Mitylene” into Word then used their word count feature). One interesting aspect of Lord Ruthven’s (the vampire) character is that he cannot survive on just anyone’s blood; he has to feed only on the blood of those he loves. That would make an interesting twist to any vampire tale. As the Goodreads summary notes, this is also the start of the motif of the vampire as aristocratic seducer. While this story is probably of mediocre quality at best for today’s literary audiences, it is interesting from the perspective of literary history as the origin of today’s vampire stories and all the cultural offshoots that have sprung from those (such as the Goth movement). Bottom line: it’s worth taking the time to read, especially if one has an interest in the historical basis for today’s horror literature and the vampire subculture.”

Thoughts? Comments?

Horror at Project Gutenberg

If you are an avid reader (of anything) and are not familiar with Project Gutenberg (http://www.gutenberg.org/wiki/Main_Page), you are doing yourself a great disservice. As they state on their homepage:

“Project Gutenberg offers over 46,000 free ebooks: choose among free epub books, free kindle books, download them or read them online.

We carry high quality ebooks: All our ebooks were previously published by bona fide publishers. We digitized and diligently proofread them with the help of thousands of volunteers.

No fee or registration is required, but if you find Project Gutenberg useful, we kindly ask you to donate a small amount so we can buy and digitize more books. Other ways to help include digitizing more books,recording audio books, or reporting errors.

Over 100,000 free ebooks are available through our Partners, Affiliates and Resources…Our ebooks may be freely used in the United States because most are not protected by U.S. copyright law, usually because their copyrights have expired. They may not be free of copyright in other countries. Readers outside of the United States must check the copyright laws of their countries before downloading or redistributing our ebooks. We also have a number of copyrighted titles, for which the copyright holder has given permission for unlimited non-commercial worldwide use.”

As they state, most of these books are available because their copyrights have expired, making them usually quite dated. However, for anyone with a bent for the historical, Project Gutenberg is a gold mine. I did a quick search for “horror” on their website and received 169 titles in response. For a few, the only relation to the horror genre was the word “horror” in the title (such as “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All its Phases–which is a horrible subject, but is non-fiction vs. horror fiction). However, many are the classics or founding works of the horror genre, such as Frankenstein by Mary Shelley, Dracula by Bram Stoker, The Vampyre: a Tale by John William Polidori, The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson, Fantome de’l Opera (Phantom of the Opera) by Gaston Leroux, many works by Edgar Allan Poe, The Great God Pan by Arthur Machen, The King in Yellow by Robert W. Chambers, The Shunned House by H.P. Lovecraft, and many others.

Please take the time to visit this treasure trove of literature and of the horror genre, and if you are so inclined, please consider making a donation (via their website) to support their worthy cause.

Thoughts? Comments?

Selections from The Writer’s Home Companion

The other day I happened to find my copy of The Writer’s Home Companion (by James Charlton and Lisbeth Mark, 1987), which I had lost/forgotten some time back. I have been perusing it since and have found several anecdotes on various authors of horror, which had not captured my attention when I purchased the book, because I was not interested in writing horror at the time. I am quoting them below for your entertainment and consideration. They provide a few insights and lessons into the art and business of writing as well as into the lives of writers, if not in the art of horror specifically. If you would like to read more of the book, you can probably find a copy at your local library or half-price bookstore.

“Edgar Allan Poe opted to self-publish Tamerlane and Other Poems. He was able to sell only forty copies and made less than a dollar after expenses. Ironically, over a century later, one of his self-published copies sold at auction for over $11,000.”

at Comicon, 2007

Photo by Penguino

“Stephen King sent his first novel to the editor of the suspense novel The Parallax View. William G. Thompson rejected that submission and several subsequent manuscripts until King sent along Carrie. Years later some of those earlier projects were published under King’s pseudonym Richard Bachmann, and one was affectionately dedicated to ‘W.G.T.'”

“Edgar Allan Poe perpetrated a successful hoax in the New York Sun with an article he wrote in the April 13, 1844 edition of the paper. He described the arrival, near Charleston, South Carolina, of a group of English ‘aeronauts’ who, as he told the story, had crossed the Atlantic in a dirigible in just seventy-five hours. Poe had cribbed most of his narrative from an account by Monck Mason of an actual balloon trip he and his companions had made from London to Germany in November 1836. Poe’s realistically detailed fabrication fooled everyone.”

Portrait by Girolamo Nerli

(1860-1926)

“Robert Louis Stevenson was thrashing about in his bed one night, greatly alarming his wife. She woke him up, infuriating Stevenson, who yelled, ‘I was dreaming a fine bogey tale!’ The nightmare from which he had been unwillingly extracted was the premise for the story of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.”

“Amiably discussing the validity of ghosts, Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley decided to try their poetic skills at writing the perfect horror story. While nothing came of their efforts, Shelley’s young wife, Mary Wollstonecroft, overheard the challenge and went about telling her own. It began ‘It was on a dreary night of November that I beheld the Accomplishment of my toils.’ Her work was published in 1818, when she was twenty-one, and was titled Frankenstein.”

“Edgar Allan Poe was expelled from West Point in 1831 for ‘gross neglect of duty’. The explanation for his dismissal had to do with his following, to the letter, with an order to appear on the parade grounds in parade dress, which, according to the West Point rule book, consisted of ‘white belt and gloves.’ Poe reportedly arrived with his rifle, dressed in his belt and gloves–and nothing else.”

Portrait by Henry William Pickersgill

“Traveling along the Italian Riviera, Lord Bulwer-Lytton, done up in an embarrassingly elaborate outfit, acknowledged the stares of passersby. Lady Lytton, amused at his vanity, suggested that it was not admiration, but ‘that ridiculous dress’ that caught people’s eyes. Lytton responded, ‘You think that people stare at my dress and not at me? I will give you the most absolute and convincing proof that your theory has no foundation.’ Keeping on only his hat and boots, Lytton removed every other article of clothing and rode in his open carriage for ten miles to prove his point.”

If you have anecdotes about your favorite authors that you would like to share, please do.

Questions? Comments?

Dr. Polidori and “The Vampyre”

1819

(Note handwritten attribution to Lord Byron)

On June 22, I was continuing my reading of Lovecraft’s “Supernatural Horror in Literature” when I encountered an interesting tidbit. When Mary Shelley was writing Frankenstein in the famous competition with her husband, Percy Shelley, and Lord Byron, another competitor was Dr. John William Polidori, whose story story from that competition, “The Vampyre”, went on to be the only other work of that competition that went on to achieve any sort of renown (according to Lovecraft).

Wikipedia has an interesting explanation for the title page above:

“The Vampyre” was first published on 1 April 1819 by Henry Colburn in the New Monthly Magazine with the false attribution “A Tale by Lord Byron“. The name of the work’s protagonist, “Lord Ruthven“, added to this assumption, for that name was originally used in Lady Caroline Lamb‘s novel Glenarvon (from the same publisher), in which a thinly-disguised Byron figure was also named Lord Ruthven. Despite repeated denials by Byron and Polidori, the authorship often went unclarified…Later printings removed Byron’s name and added Polidori’s name to the title page.

Go to this link for the Project Gutenberg etext of “Vampyre”. Modern printings can be found at the Open Library.

1795-1821

(from Wikimedia)

Another couple of interesting notes from the Wikipedia article on The Vampyre:

“The story was an immediate popular success, partly because of the Byron attribution and partly because it exploited the gothic horror predilections of the public. Polidori transformed the vampire from a character in folklore into the form that is recognized today—an aristocratic fiend who preys among high society.[1]“

“Polidori’s work had an immense impact on contemporary sensibilities and ran through numerous editions and translations. An adaptation appeared in 1820 with Cyprien Bérard’s novel, Lord Ruthwen ou les Vampires, falsely attributed to Charles Nodier, who himself then wrote his own version, Le Vampire, a play which had enormous success and sparked a “vampire craze” across Europe. This includes operatic adaptations by Heinrich Marschner (see Der Vampyr) and Peter Josef von Lindpaintner (see Der Vampyr), both published in the same year and called “The Vampire”. Nikolai Gogol, Alexandre Dumas, and Alexis Tolstoy all produced vampire tales, and themes in Polidori’s tale would continue to influence Bram Stoker‘s Dracula and eventually the whole vampire genre. Dumas makes explicit reference to Lord Ruthwen in The Count of Monte Cristo, going so far as to state that his character “The Comtesse G…” had been personally acquainted with Lord Ruthwen.[10]“

I find it fascinating that possibly the two greatest motifs in the history of horror literature (Frankenstein and vampires) were started at the same friendly competition between four friends.

Unfortunately, Dr. Polidori did not live to see the success of the literary phenomenon he created. The article goes on to note:

“He [Polidori] died in London on 24 August 1821, weighed down by depression and gambling debts. Despite strong evidence that he committed suicide by means of prussic acid (cyanide), the coroner gave a verdict of death by natural causes.[3]“

The Canon of Horror

Illustration by Arthur Rackham, 1935

I was just musing that if a canon of horror literature could be developed, what should it include? This would be a collection of say ten works that define horror literature and that everyone seriously interested in horror should read if he/she they wish to learn what horror is and should be. This would not be a collection of the most popular works (whether novel, short story, essay, screenplay, theater, etc.) of horror, which would change constantly, but ten works which would define horror now and forever as the Bible does Christianity, as the Koran does Islam, and as the Analects of Confucius do Confucianism. These should be eternal works that at the end of time, after the Zombie Apocalypse when no more books are written, the few remaining survivors of humanity can review all the literary works of all time and say, “These ten defined the horror genre.” Of course, this canon will be forever debated, but lively, engaged discussion is the fun of a list like this.

To start off this conversation, here are my initial ten recommendations (subject to change as my reading progresses). I will keep this list to one work from each of ten authors so that works by one author do not overwhelm the list. This is not in any order of priority or preference–just as they pop into my mind. Although these reflect my own reading (which tends to the past more than the present), I have added one or two authors I haven’t read, but from what I understand, have made significant contributions to the horror genre.

- “The Tell-Tale Heart” by Edgar Allen Poe

- Books of Blood by Clive Barker

- Carrie by Stephen King

- Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

- “The Shadow over Innsmouth” by H.P. Lovecraft

- “Lukundoo” by Edward Lucas White

- “The Sandman” by E.T. A. Hoffmann

- Dracula by Bram Stoker

- “The Willows” by Algernon Blackwood

- Psycho by Robert Bloch

- I am Legend by Richard Matheson