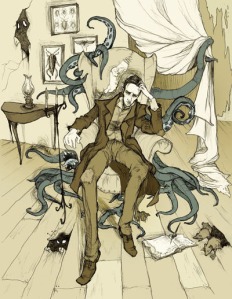

Photo by JaSunni, 2008

On Monday, I learned of the death of Richard Matheson, one of the great horror writers of the twentieth century. As my tribute to him, here are a few quotations from and about him along with a few examples on how he generated his ideas. There were a lot, so I picked the ones that seemed most philosophical about writing and life in general in order to get a feel for the man behind the writing.

From Goodreads:

“What condemnation could possibly be more harsh than one’s own, when self-pretense is no longer possible?” ― Richard Matheson, What Dreams May Come

“We’ve forgotten much. How to struggle, how to rise to dizzy heights and sink to unparalleled depths. We no longer aspire to anything. Even the finer shades of despair are lost to us. We’ve ceased to be runners. We plod from structure to conveyance to employment and back again. We live within the boundaries that science has determined for us. The measuring stick is short and sweet. The full gamut of life is a brief, shadowy continuum that runs from gray to more gray. The rainbow is bleached. We hardly know how to doubt anymore. (“The Thing”)” ― Richard Matheson, Collected Stories, Vol. 1

“If men only felt about death as they do about sleep, all terrors would cease. . . Men sleep contentedly, assured that they will wake the following morning. They should feel the same about their lives.” ― Richard Matheson, What Dreams May Come

“In a world of monotonous horror there could be no salvation in wild dreaming.” ― Richard Matheson, I Am Legend

“Now when I die, I shall only be dead.” ― Richard Matheson, I am Legend and Other Stories

From Wikiquotes:

I think What Dreams May Come is the most important (read effective) book I’ve written. It has caused a number of readers to lose their fear of death — the finest tribute any writer could receive. … Somewhere In Time is my favorite novel.

“Ed Gorman Calling: We Talk to Richard Matheson” (2004).

From Uphillwriting.org:

If you go too far in fantasy and break the string of logic, and become nonsensical, someone will surely remind you of your dereliction…Pound for pound, fantasy makes a tougher opponent for the creative person.

– Richard Matheson

And here are a couple of quote about Matheson–also from Wikiquotes:

Matheson gets closer to his characters than anyone else in the field of fantasy today. … You don’t read a Matheson story — you experience it.

Robert Bloch, as quoted in an address by Anthony Boucher (29 August 1958), at the “Solacon”, the 1958 Worldcon

He has many … virtues, notably an unusual agility in trick prose and trick construction and a too-little-recognized (or exercised) skill on offtrail humor; but his great strength is his power to take a reader inside a character or a situation.

Anthony Boucher in an address at the “Solacon”, the1958 Worldcon (29 August 1958)

Wikipedia offers an interesting paragraph on how Matheson came up with the ideas for some of his more famous works:

Matheson cited specific inspirations for many of his works. Duel derived from an incident in which he and a friend, Jerry Sohl, were dangerously tailgated by a large truck on the same day as the Kennedy assassination. (However, there are similarities with William M. Robson’s script of the July 15, 1962 episode of the radio drama, Suspense, “Snow on 66”.[citation needed]) A scene from the 1953 movie Let’s Do It Again in which Aldo Ray and Ray Milland put on each other’s hats, one of which is far too big for the other, sparked the thought “what if someone put on his own hat and that happened,” which became The Shrinking Man. Bid Time Return began when Matheson saw a movie poster featuring a beautiful picture of Maude Adams and wondered what would happen if someone fell in love with such an old picture. In the introduction to Noir: 3 Novels of Suspense (1997), which collects three of his early books, Matheson said that the first chapter of his suspense novel Someone is Bleeding (1953) describes exactly his meeting with his wife Ruth, and that in the case of What Dreams May Come, “the whole novel is filled with scenes from our past.”

Thoughts? Comments?