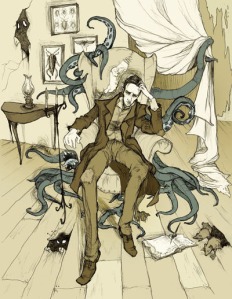

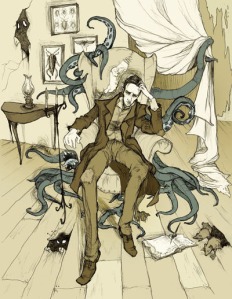

H.P. Lovecraft by Mirror Cradle

I like the illustration above, not only because it shows Lovecraft in the throes of creation, but also because it can be a metaphor for anyone in the deepest and darkest of contemplations or beset with a multitude of woes. For now, though, I will say that it represents Lovecraft contemplating today’s question which is: forget everything you have ever read about horror, what is horror to you?

Stephen King made this comment (I found it on goodreads.com):

“The 3 types of terror: The Gross-out: the sight of a severed head tumbling down a flight of stairs, it’s when the lights go out and something green and slimy splatters against your arm. The Horror: the unnatural, spiders the size of bears, the dead waking up and walking around, it’s when the lights go out and something with claws grabs you by the arm. And the last and worse one: Terror, when you come home and notice everything you own had been taken away and replaced by an exact substitute. It’s when the lights go out and you feel something behind you, you hear it, you feel its breath against your ear, but when you turn around, there’s nothing there…”

To me, these seem to be the superficialities of terror and horror. If we use disease as a metaphor for horror, then these are its symptoms. The virus lying at the root of horror is man’s inhumanity to man. Seeing a severed head tumbling down stairs is indeed horrible; seeing the murderer sever the head would be even worse, but being able to look into the soul of the murderer and see that the motive for the act stems from the murderer’s complete indifference to the suffering of others would be even worse. Perhaps even worse than that would be seeing that that indifference to others is not uncommon.

Many have speculated on what fascinates people about horror. Why would anyone enjoy being frightened? An article I read last night (I think from Wikipedia) says essentially (I am summarizing in my own words) that it is because the security our civilization our modern society affords us has eliminated the need for the primal fear that developed as a survival mechanism during the early days of evolution. That may be true to some degree, but if society eliminated some fears, it instilled others. How many have seen the movie “Candyman”? How many have seen “I am Legend?” or “The Omega Man” (both derive from the novel “I am Legend” by Richard Matheson), which is only one example of post-apocalyptic literature that would have been inconceivable in primeval times.

Instead of some overreaching drive extending throughout mankind, it may be that the need simply stems from the fact that the adrenaline rush, the focus on the moment, the muscle tension, and all the other physical sensations experienced during fright are the same or very similar to those experienced during sex, but without the sexual arousal itself. These are also similar to the sensations experienced during peaks of athletic activity. I was in the martial arts for many years and I can testify that the adrenaline rush experienced during sparring matches or when one is performing at peak ability can be addicting. Being frightened puts one on a similar level of physical and mental awareness, because it is an instinctual preparation to fight as if one is actually being threatened. The great thing about horror though is that while one enjoys all the physical highs of one’s body revving up for action, there is no actual threat. Everyone is safe. Candyman is not actually going to come out of the screen and track you down (though your subsequent nightmares may tell you otherwise).

So, please put yourself in Mr. Lovecraft’s place in the illustration above and ask yourself, what is horror?