Photo by Phil Slattery

Someone once said that poetry is the “illumination of the particular”.

In 1992, when I was enamored of poetry and was striving to become a serious poet, I took that advice to heart and wrote the poem “Faust“, which describes the thoughts of the infamous Dr. Faust immediately after signing over his soul to Mephistopholes in exchange for all knowledge. What I describe there is everything that is going through Faust’s mind in a few seconds, the amount of time it takes to actually read the poem. The hardest part for me was to choose the right moment to illuminate. I could have chosen the moment before signing or a moment a year later or the moment when he first met Mephistopholes or an infinite amount of others. But that second seemed the most pregnant with meaning, because it is the moment realizes that what he has done can never be undone and that he has lost everything meaningful as a result. After that I just had to work out the details of what he had lost, the sensations he was experiencing, the future consequences, and the wording, all of which took about a solid eight hours. Choosing the particular moment to illuminate was the critical decision in construction of the poem.

Good prose is often compared to poetry. When Ray Bradbury was introduced to Aldous Huxley at tea after publication of The Martian Chronicles in 1950, Huxley leaned forward and asked Bradbury, “do you know what you are? You are a poet.” “I’ll be damned,” responded Bradbury.

I believe that good writing (both prose and poetry) is like good photography: it illuminates the particulars in the subject so that the viewer sees them in their abundant wonder for the first time, though he may have seen that scene a thousand times before. Take the photo at the top of the page for example. I happened to see a scorpion crawling across a floor one day (when I was heavy into nature and wildlife photography), grabbed the nearest camera, lined up the shot as best I could, and snapped it. To my surprise, the focus and lighting came off better than I had planned, and thousands of details popped out in the photo that I had never anticipated. I had walked across that floor tile I do not know how many thousands of times previously and I had never noticed the texture in its surface. I had never been as close to a scorpion before either and I was amazed at the details that popped out in it.

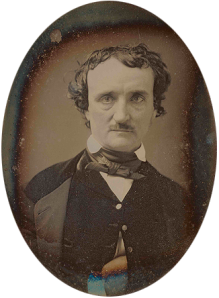

Great writers seem to have an innate sense for the proper amount of details and how to use them. Among writers of horror, Poe springs to mind immediately as a master of detail with “The Tell-Tale Heart” as a prime example of how he used details. Poe seems to string together a series of moments (describing the old man’s eye, creeping through the door to the old man’s bed, killing him, listening to the heart as it beats beneath his floorboards) and illuminates the details in each to produce a story of tremendous power. But among all these, is there a single, superfluous detail that does not heighten the drama? No. Poe knew which details to illuminate and how to illuminate the details in each of those.

Several years ago, I saw a biography of Napoleon Bonaparte on A&E. One of the speakers was an instructor at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. He said that one thing Bonaparte recognized was that “while details are important, not all details are important.” I found this a fascinating point as the speaker went on to point out that Bonaparte had a incredible memory for details. For example, every two weeks he had the roster of the entire French army (about 200,000 troops) read out to him. He could remember from sitting to sitting who was sick, dead, missing, and so forth. He could ask detailed questions about the state of repair of equipment such as “last time the second gun of the third battery at Cherbourg had broken spokes in its left wheel, has that been fixed yet?”

I try to remember that these days as I write, so that I weed out the important details from the unimportant ones.

“But which details are important?” you ask. I wish I could give a quick and easy answer on that. At this point in my development as a writer (I may give a completely different answer years from now when my learning has progressed further), I would say: (1) details that help the reader live the story vicariously, such as sensations, (2) details that help the reader understand the current situation and its implications, and (3) details to help the reader understand the characters, their thoughts, their perspectives, and their reactions, (4) details that tie the parts of the story together, such as a motif, and create unity, and (5) details that point toward a denouement.

Details can be critical in writing, but as with all other things, there must be a balance. Drown the reader in details and the story becomes tedious. Provide too few details, and the story becomes monotonous. Choose the wrong details, and the story is boring. Choose the right details and the reader can step into another world.

Thoughts? Comments?